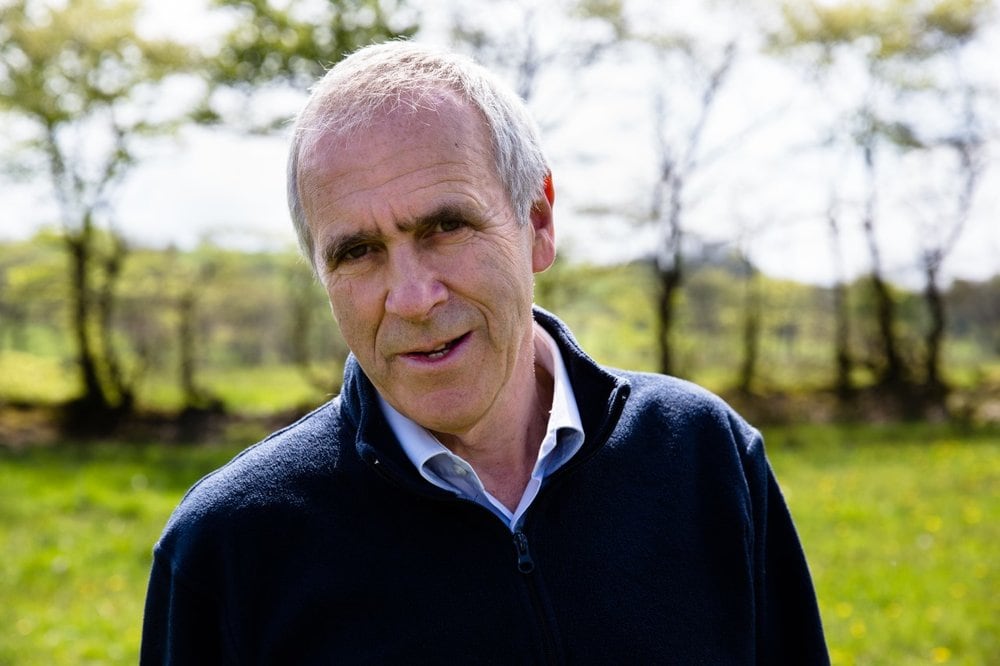

Patrick Holden is quite the visionary. With the longest established organic dairy farm in Wales, he’s no stranger to agriculture - but with a heart firmly rooted in sustainability.

When in conversation with Patrick Holden you immediately sense he’s a fountain of knowledge, likely due part passion – part exceptional career experience.

As a *brief* introduction: he was founding chairman of British Organic Farmers back in 1982, where he drafted the world’s first organic dairy standards later adopted by the UK government and EU regulations. He was the director of the Soil Association (UK’s leading organic certification body) during which time the organisation developed the market and standards for organic food. He has a CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) for his contributions to organic farming, and, now, is the founding director of the Sustainable Food Trust – an organisation dedicated to catalysing change to accelerate the transition globally to more sustainable food systems. Phew!

Oh, and did I mention he also sells one of the most popular cheddar cheeses around – Hafod – from his own herd of eighty-five Ayrshire cows (a native bread from Scotland), at legendary Neal’s Yard Dairy?

I had the pleasure of being lectured by him in London during my culinary studies, and sat intently for the three hours as he led the way through the murky depths of food sustainability, and our pressing need as a global planet to act – and boy, did he get my brain ticking. After reaching out and connecting, I was delighted, and honoured, to conduct the guest interview below.

There’s no doubt that, in general, developing more sustainable food systems, is a complicated and challenging topic. But, it’s so important we have more conversations about it, raise awareness, and encourage each other to do research. After all, we have one precious planet🌎.

I hope this will be the start of many more articles on my blog around food sustainability. Thanks Patrick for kicking me off. Without further ado…

What do you believe sustainable food production is? What questions do you think we should ask around whether a food has been sustainably produced?

Sustainable food production is many things. It’s about applying the principal of working in harmony with nature to our food farming system. It’s the minimal use of non-renewable or polluting inputs (e.g. fertilisers, pesticides…). It’s using diversity to mimic nature, through means like crop rotation (the practice of growing different types of crops in the same area in sequenced seasons; helping to manage soil fertility, and minimise disease and pests). It’s building the health of the soil and its fertility, in turn nourishing the plants and animals that depend on these cycles.

We need to ask questions like who produced my food and where did they live? What is its provenance? How was it produced? If we know where our food comes from – the farmer who produced it and how sustainable their practises are – then I believe we’re both powerful and empowered with our food choice. Nowadays we can go into supermarkets and say here’s my buying prescription, this is what’s important to me. If all of us did that our food system would change instantly. However, the problem is few of us do this – and it has become incredibly hard, from a transparency perspective, to have those questions answered when you’re buying – which is shocking.

What are some key reasons for rethinking our current food system?

We’re facing irreversible elements of climate change ahead with biodiversity loss threatening nature, increasing migration and food security linked to conflict, and an inefficiently around how we process and distribute food leading to large amounts of waste. I don’t believe it’s more food we need to produce, but rather producing it in different ways, and changing our diets to align them to be more in harmony with nature and the staple foods we can grow.

Many of us may not realise the major contribution that food and farming can have on greenhouse gas emissions. This can occurs in many different way; for example, nitrous oxide emissions occurring from excessive nitrogen fertiliser use (a significant greenhouse gas due to its potency), the manufacture of these fertilisers, the fossils fuels used to run industrial agriculture, and the release of carbon from soil carbon banks.

I believe modern agriculture has, in many ways, become a kind of mining operation. Nitrogen fertilisers are used to stimulate plant growth, which enables farmers to continuously grow crops each year. However, with traditional farming systems there tended to be a rotation, with periods of building up the soil and fertility, followed by a cropping phase of releasing the fertility you’ve built up – but with nitrogen fertiliser, a crop rotation isn’t needed.

The down side here is that this system breaks down organic matter in topsoil faster (where most of the earths biological activity occurs), with topsoil being one of the worlds biggest carbon banks – a precious commodity, which sees carbon dioxide taken from the air by plants in order to grow, and then released into the soil as they decompose. Environmentally, this is concerning.

Across all of these issues we have to look at the predominate land user, which is agriculture. If we want to change, we must rethink the ways we’re farming and producing food.

You talk a lot about the true food cost of food under your organisation The Sustainable Food Trust. This is an interesting consideration when perceiving food, and one that holds great merit – can you expand?

When we buy food we assume the cost we pay in shops reflects the true cost of product – which seems a reasonable proposition.

However, and what we may not realise, is that some methods of food production cause environmental damage, and without financial accountability from producers. This might include water pollution, soil degradation, loss of biodiversity, antibiotic resistance, and then the overall contribution on climate change. Additionally, there’s the impact food quality has on public health, which isn’t costed into cheap, but nutrient-poor, food.

So, if we adjusted costs, some adherently cheap foods aren’t actually cheap, but rather much more expensive in terms of wider impact. Economists call these externalities – consequences of a system that aren’t reflection in price, but that affect other parties.

Of course, we pay for these in hidden ways. Medical bills, taxes for environmental clean up, as well as the costs deferred to future generations and other countries. Whereas, when we use sustainable methods of food production, we could consider THIS price a true representation. For more on this, check out the Hidden Cost of Food.

How might this influence buying power?

Food cost is really the single reason why the organic market hasn’t taken off to become mainstream – the price differential between a truly costed product (e.g. an organic chicken) can be so high that only a small percentage of people can afford to pay that much more.

We may want to support these practices, but can’t afford to do it or don’t think money can be made doing it (e.g. as a farmer, food processor or retailer too). This is completely understandable, as we don’t have limitless income.

Our buying potential is one of the most powerful things in the world – but if the gap is too much, even if we’re deeply idealistic, there’s a limit to how much extra we can pay for food. We need to really correct these uncosted negative externalities – this doesn’t mean banning production methods, but by other means like considering a ‘polluter pays’ principal e.g. taxes for producers (e.g. for the damage caused by nitrogen fertiliser use) which would naturally bring the price of some foods up, making other products that don’t use these methods more price competitive.

In doing so, cheap food will cost more, but be more reflective of it’s true cost – then saving cost on the national health system, water pollution clean-up etc.

If we were to align future diets with sustainable food systems what do you think this might this look like?

At the moment there is huge shifts in dietary preferences in response to environmental concerns, with many people shifting to exclusively plant-based diets. My response to this is we should be thinking more of what the land can produce in the places we live.

If we go plant-based, but source our vegetable oils from rainforests far away or eat almonds from the central valley in California while in the UK- in other words, still follow diets based on unsustainable farming practises on the opposite end of the world – have we switched to be part of the solution, or yet still the problem?

The answer, I believe, is to do some research to find out what would be produced if the country was converted to sustainable production, and additionally the proportions of food produced. Then to consider eating more to this, while supporting more sustainable food production practises. If we buy wisely, choosing carefully the system needed to replace the one we have right now, adjusting our diet accordingly, we can make a positive difference.

We must keep in mind that as consumers, unless we eat it, farmers can’t switch to sustainable agriculture. A farmer converting to sustainable practises would need a fertility building part of their rotation, which, for example, may be a 7 year rotation with 3-4 years growing grass and clover to build fertility. What will they do with the grass and clover during the fertility building phase? They can turn it into food by grazing animals that can consume a diet from it, like sheep, beef and dairy cattle (wonderfully, grass-fed meat also has an incredible nutritional composition). Supporting farmers converting to sustainable farming practises is key.

This is also importantly how the fertility of some of the worlds most fertile soil is built, by the interaction between grass and ruminates. Many aren’t aware of this crucial interaction, and that this is the food these animals are designed to eat, rather than a grain-fed diet, common in intensive farming. I believe the focus needs to be the reduction of the consumption of the ‘wrong’ kind of produced meat, as well as intensively-produced dairy products – and instead switching to foods produced by sustainable practises.

From a practically sense, what can we do – as a consumer – right now, to make positive change?

- As consumers, we hold great power, simply because we buy food. If enough of us changed what we buy, the food system would have to change too. So, whenever food shopping, ask yourself the question “what can I buy, that I already buy, in a way that I will become a part of the solution, not the problem?”.

- When making sustainable changes to your diet, start with what means the most to you or the foods you eat often. You’ll enjoy it more when you know it has been produced more sustainably, it’ll be more nutrient-dense and of course flavoursome. In the case of meat, this may come with extra cost – but it’s better to buy less anyway, just better quality.

- If you can, try and source food as directly from producers. If you cut one or two links in the food chain, the foods you buy may become more affordable! In London, check out farmers markets, box schemes (e.g. Riverford, Abel & Cole), or mail order systems directly from farms e.g. freezer boxes of meat.

- When it comes to commonly consumed staple foods, choose in-season wherever you can and buy as locally as possible, from a known farmer ideally or one with a known and trusted certification scheme e.g. organic, biodynamic or fair trade (the latter for the social & cultural side).

- Ask more questions about your food. Learn more, know more, do more. We are what we eat!

If we all did this, we could change the world.

To end on a note of great positivity from Patrick:

“My generation is the binge generation – we have dined out on the resources of planet earth, without thinking, and knowing, there was a problem. Now your generation is inheriting this mess, and we have to put it right. There is no doubt a shift in awareness, across millennials, which is very powerful – you think in a different way, you’re more intuitively aware of the problems your generation has inherited, you’re less brand loyal, you ask tough questions, and you see behind things – which give rise to huge optimism for millennials and the next generation.”

No Comments